The link between greenhouse gases and climate change is well understood and documented. However, Earth’s heat budget – the balance between incoming solar radiation and outgoing heat – is complex and impacted by a variety of human activities and natural mechanisms.

All the heat contributing to global warming starts with the Sun’s radiation. Upon approaching the Earth, anything that interacts with that light potentially impacts the climate. Aerosols are microscopic particles suspended in the Earth’s atmosphere. Depending on their composition, they reflect or absorb sunlight – respectively cooling or heating the Earth. In total, clouds and aerosols reflect about a third of the radiant energy. This cooling effect is known as the parasol or albedo effect. The remaining energy is then absorbed into the Earth's atmosphere and surface as heat.

Photo taken aboard Space Shuttle Atlantis in August 1991, showing a layer of aerosols from the June 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo. Credit: Image courtesy of the Earth Science and Remote Sensing Unit, NASA Johnson Space Center

Varying in size from a few nanometers to 100 microns, atmospheric aerosols have natural sources, including sea spray, wildfire smoke, and volcanoes, and anthropomorphic sources, such as burning fossil fuels and biomass, industrial processes, agriculture, and transportation. The emissions coming from modern technologies like cars and factories have greatly increased the quantity of particulate matter in the atmosphere. On average, several million tonnes of aerosols are emitted globally every day.

Other aerosol sources have natural origins that are accelerated by human activity. Desert winds aerosolise dust as they have for billions of years; however, increased land and water use is leading to desertification and more dust.

Aerosols encourage cloud formation as moisture condenses around the aerosol particles to crystallise into clouds. Aerosols created by human industrial processes tend to create denser clouds with smaller droplets, increasing the reflectivity of the cloud and extending its lifetime. In other words, more clouds that can reflect more heat.

In fact, aerosol air pollution has made the planet about 0.7° F (0.4 °C) cooler than it otherwise would be, according to the 2021 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Over that same period, greenhouse gas emissions have added 2.7°F (1.5°C) of warming.

So if aerosols help cool the planet… is air pollution good?

In short, no. While it’s true that the efforts to reduce emissions may have caused a temporary warming effect, the long-term benefits of reducing greenhouse gases will far outweigh short-term heating. Above all, air pollution is detrimental to biological health, leading to breathing problems, acid rain and other concerns.

Furthermore, not all aerosols have a cooling effect. Soot is made of dark particles of carbon from burning fossil fuels, or plants. These dark particles absorb sunlight and warm the atmosphere. When soot eventually settles onto snow or ice, it darkens the surface, which reduces its reflectivity and absorbs more heat, increasing the melting rate. Also, aerosols may play a role in producing or destroying gas species, such as ozone, by acting as a surface catalyst for chemical reactions.

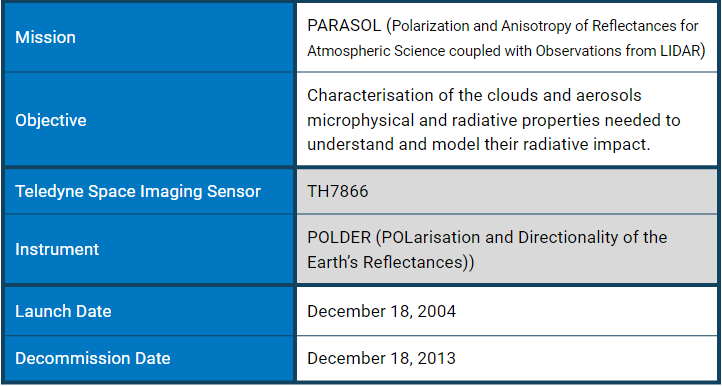

Launched in December of 2004, CNES’s PARASOL mission (Polarization and Anisotropy of Reflectances for Atmospheric Science coupled with Observations from LIDAR) tracked the vertical and temporal distribution and microphysical characteristics of aerosols. PARASOL evaluated their influence on solar radiation by determining the quantity and size distribution of aerosols over oceans and their turbidity index over land surfaces. It also looked at other data points, including thermodynamic phase, chemical composition, altitude, optical thickness, estimated reflected solar flux and water vapour content.

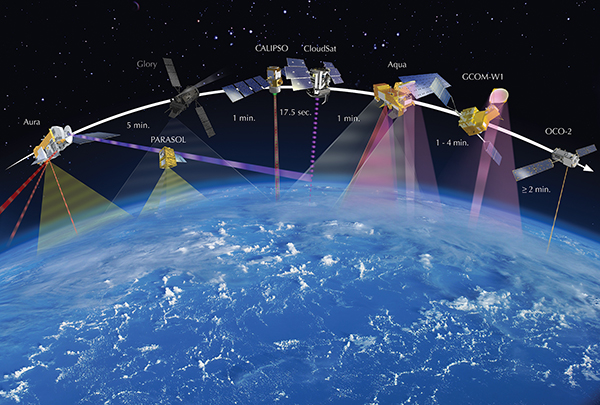

Illustration of the A-train formation around June 2011. Credit: NASA

PARASOL was a part of CNES’s Myriade microsatellite series and was also a part of NASA’s A-Train constellation of satellites. Designed to work together and synergise data collection, these satellites had, for the first time, combined a full suite of instruments for observing clouds and aerosols, from passive radiometers to active lidar and radar sounders. This collaboration allowed scientists to obtain data points on unplanned parameters, such as the macro-physical properties of clouds – altitude and geometrical thickness – and to characterise aerosol plumes over cloudy areas.

Researchers use predictive models to understand how the interplay between aerosols and clouds impact the climate system. PARASOL helped answer uncertainties about the radiative impact of clouds and aerosols to update the climate models used to estimate the amplitude, speed and geographic distribution of global warming. The data also helped models determine the size and shape of particles depending upon the given conditions.

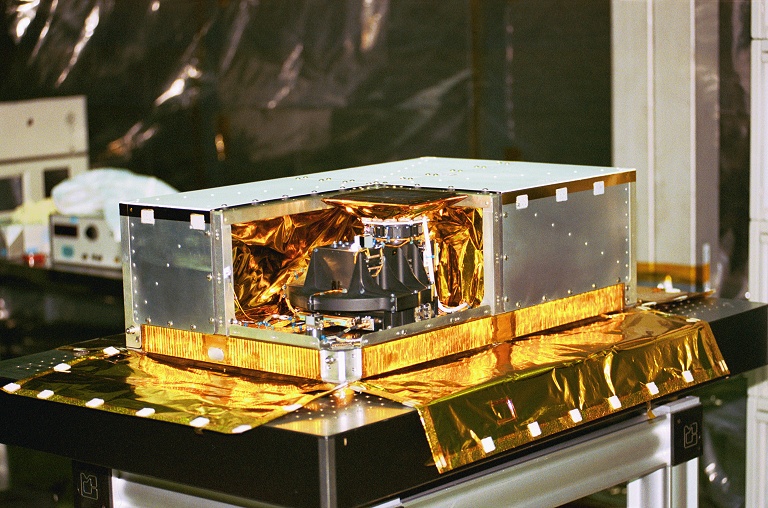

POLDER (POLarisation and Directionality of the Earth’s Reflectances)

Solar radiation becomes polarized when scattered by certain particles such as aerosols, water droplets or ice crystals. The POLDER radiometer onboard PARASOL measured the directional and polarized properties of visible and near-infrared solar radiation to characterize clouds and aerosols. This process is more accurate than traditional methods only relying on spectral signatures. Importantly, POLDER could also gather accurate data over bright surfaces such as snow.

Cut-away view of the POLDER-P instrument. Credit: ICARE

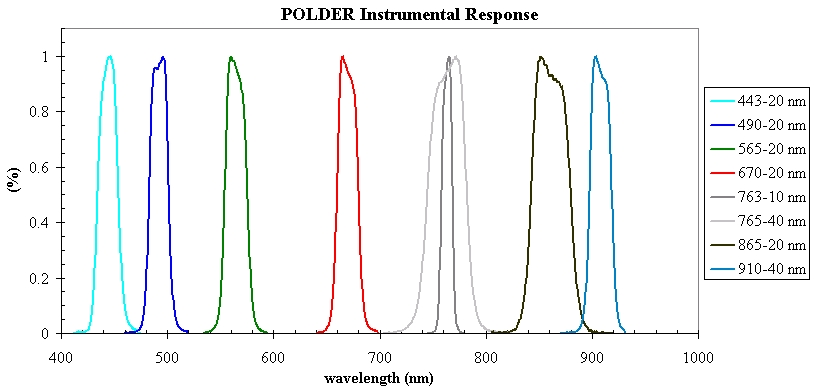

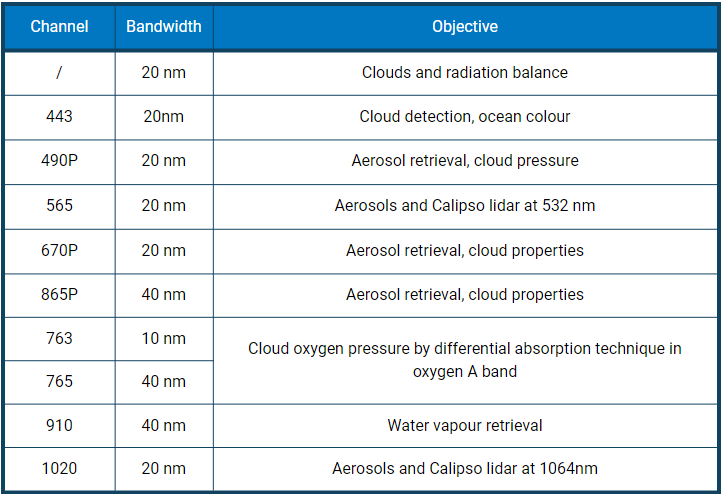

POLDER consisted of a digital staring camera with a 274 x 242 pixel Teledyne e2v TH7866 CCD detection array, with wide field-of-view telecentric optics and a rotating wheel carrying spectral and polarised filters. The instrument had nine spectral channels(443, 490, 565, 670, 763, 765, 865, 910 and 1020 nm), three of which – 443, 670, and 865 – were implemented with polarised filters.

The instrument could record the same ground target from as many as 14 angles, up to 60°, in every track, and could acquire a sequence of images every 20 seconds with a repeat cycle of 16 days. Each 2D image or scene comprised a swath of 1600 km (along-track) x 2400 km (cross-track) with a ground spatial resolution of 5.3 km x 6.2 km at nadir.

PARASOL’s POLDER was essentially a copy of the POLDER 1/2 instruments flown on ADEOS and ADEOS-II, respectively. All three POLDER instruments contained Teledyne e2v detectors. Compared to previous iterations, the sensor array on PARSOL’s POLDER was rotated 90 degrees to favour multidirectional observation over daily global coverage. Additionally, a 1020 nm channel was added to make measurements to compare to data acquired by the lidar onboard CALISPO.

End of Mission

Compilation of the Fine Mode Optical Thickness measuring the polarized radiances created by aerosols smaller than 0.35 microns. Recorded March 2005 to mid-October 2013. Credit: AERIS/ICARE Data and Services Center.

PARASOL well outlived its two-year design life. In October 2013, it was lowered out of the A-Train constellation zone and placed in a decaying orbit where it will eventually renter the earth’s atmosphere over the next couple of decades. On December 18, 2013, exactly 9 years after its launch, CNES shut off the PARASOL satellite.

The full archive of PARASOL observations has been reprocessed in 2014 and the latest version of all products is available at the ICARE Data and Services Center.

This article is the last of a four-part series covering Teledyne Space Imaging's contributions to the A-Train:

Works Cited

Centre National d'Etudes Spatiales (CNES). (Dec. 12, 2005). Parasol: Parasol effect and greenhouse effect. CNES. https://web.archive.org/web/20060213092634/http://smsc.cnes.fr/PARASOL/dossier_presse_parasol.pdf accessed from https://web.archive.org/web/20060125025208/http://smsc.cnes.fr/PARASOL/.

eoPortal. (Jun. 11, 2012). PARASOL (Polarisation and Anisotropy of Reflectances for Atmospheric Science coupled with Observations from a Lidar). eoportal.org. https://www.eoportal.org/satellite-missions/parasol.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). (June 12, 2023). Aerosols: Small Particles with Big Climate Effects. nasa.gov. https://science.nasa.gov/science-research/earth-science/climate-science/aerosols-small-particles-with-big-climate-effects