All we can know about the history of the Universe comes from observations of light where burning orbs of gas and clouds of heat illuminate dust vapours radiating through the ether. The key to understanding how all the suns, planets, asteroids, and other celestial objects formed lies in studying how those gases flow between galaxies.

All we can know about the history of the Universe comes from observations of light where burning orbs of gas and clouds of heat illuminate dust vapours radiating through the ether. The key to understanding how all the suns, planets, asteroids, and other celestial objects formed lies in studying how those gases flow between galaxies.

While light propagates extremely fast – 299,792 km (186,282 miles) per second – the finite speed of light means that when we observe a distant object, we see the state of the object when the light left the object, not the object's state today. When viewed through a sensitive telescope, extremely distant galaxies will look as they did at their birth – transforming the telescope into a “time machine” to study how the Universe evolved.

Traditionally, astronomical optical observations have been separated into imaging and spectroscopy. Imaging can include a wide field of view with great detail, but it essentially combines together all the available light of a given point in a galaxy. Spectrographs can split that light into separate components for examination but lose spatial resolution.

The MUSE instrument at the European Southern Observatory’s VLT. Image Credit: ESO

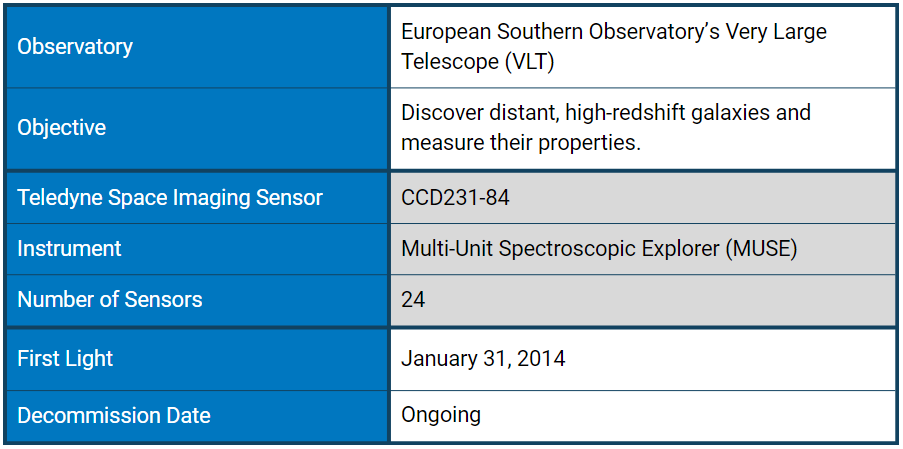

The Multi-Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE) combined a wide-field survey telescope with the measuring capabilities of a spectrograph. Installed in 2014 on the European Space Observatory’s (ESO) Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile, MUSE is an integral field spectrograph designed to produce optical 3d spectrographs of the most distant – and faint – parts of the Universe. Specifically, MUSE is attached to Yepun, the name given to one of the four 8.2-meter telescopes that make up the VLT. Yepun is what the indigenous Mapuche of Chile call Venus – the evening star.

Due to the complexity of the instrument and the need for precise alignment, MUSE was delivered to the VLT completely assembled. Weighing eight metric tons, it had to be loaded through the telescope’s observation slit. However, the modular design of MUSE means that each of the 24 IFUs can be removed for maintenance or repair using a custom-designed cradle.

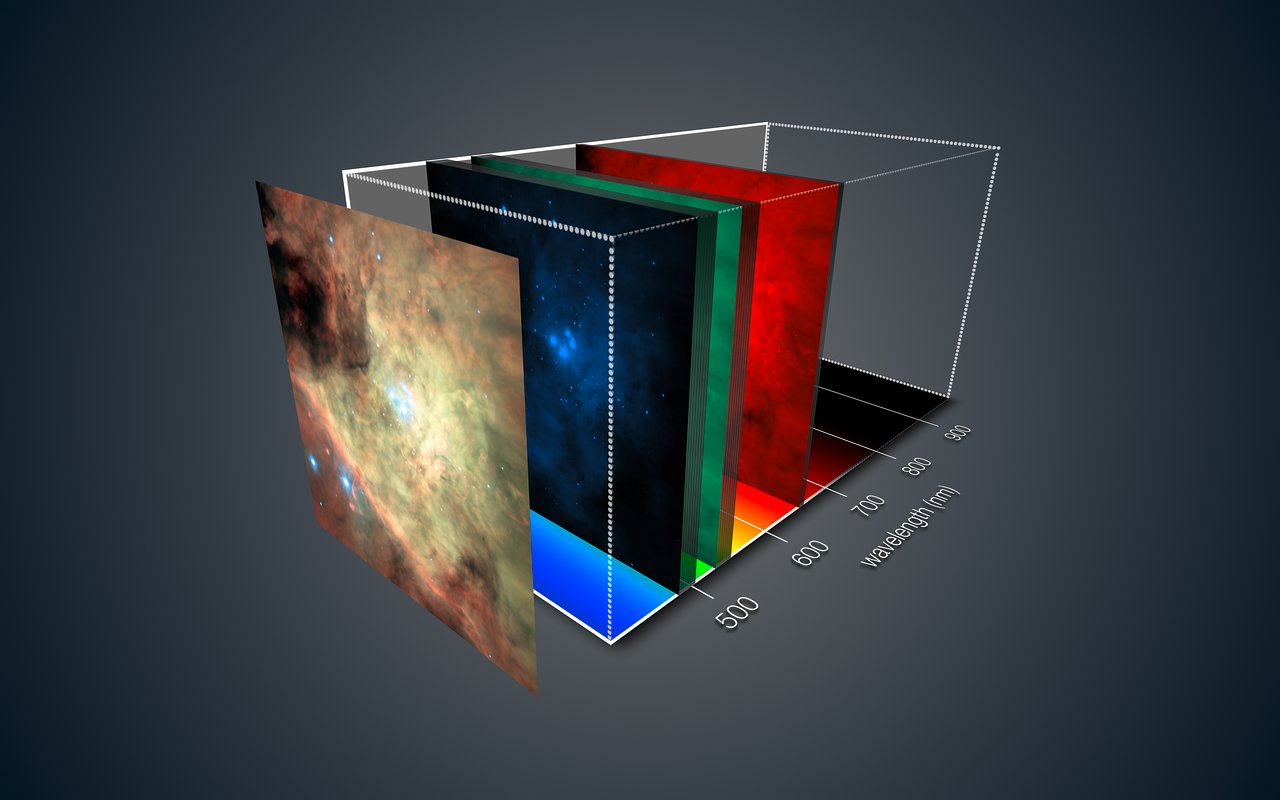

In the images produced by MUSE, each pixel measures the intensity of the light as a function of its colour or wavelength from visible to near-infrared. The instrument consists of 24 identical integral field units (IFU), each consisting of an image slicer, a spectrograph, and a Teledyne Space Imaging 2kx4k CCD detector. MUSE splits the field of view into 24 individual image segments, which are each split further into 48 mini slits. Each set of mini slits is injected into a spectrograph, which disperses the light into its constituent colours – 90,000 spectra for each complete mosaic image.

Component views that build up image of the Orion Nebula. Various views of the Orion Nebula allow astronomers to move through different views at various wavelengths. Credit: ESO/MUSE consortium/R. Bacon/L. Calçada

Component views that build up image of the Orion Nebula. Various views of the Orion Nebula allow astronomers to move through different views at various wavelengths. Credit: ESO/MUSE consortium/R. Bacon/L. Calçada

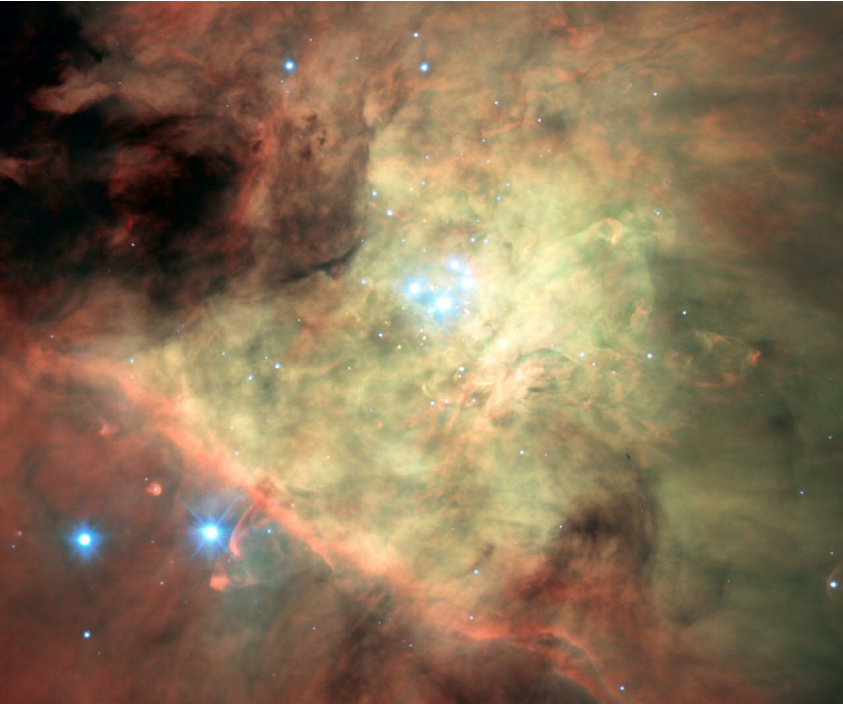

Spectral Reconstructed Image of a 6 x 5 Mosaic of the Orion Nebula. This picture is based on a mosaic of many MUSE datasets that were obtained soon after the instrument achieved first light in early 2014. Credit: MUSE/ESO Consortium / R. Bacon

Spectral Reconstructed Image of a 6 x 5 Mosaic of the Orion Nebula. This picture is based on a mosaic of many MUSE datasets that were obtained soon after the instrument achieved first light in early 2014. Credit: MUSE/ESO Consortium / R. Bacon

The unprecedented amount of spectral data allows astronomers to study the properties of different parts of an object – such as a galaxy – to see how it is rotating, measure its mass, and determine chemical composition. During the subsequent analysis, an astronomer can move through the data and study different views of the object at different wavelengths.

The precision and wide-field view of MUSE enables a new imaging technique called crowded field spectroscopy, where large spectroscopic samples are taken in the crowded environments of massive star clusters. This unlocks more detailed information about these busy areas. This technique can be particularly useful in studying collisions between galaxies.

The data collected by MUSE provides a new view of very distant galaxies as they formed just one billion years after the Big Bang. It has detected galaxies 100 times fainter than in previous surveys, deepening the scientific understanding of galaxies across cosmic time.

Lyman-Alpha Emitters: Reimaging Hubble Deep Field

Credit: ESO/MUSE HUDF collaboration

Lyman-alpha emitters are thought to be the progenitors of most modern Milky Way-type galaxies. Detected by using the Lyman-alpha emission line – the brightest line emitted by hydrogen gas – an image taken of those very distant objects shows infant galaxies as they began to form.

As light travels a long distance, the wavelengths will stretch out of the visible spectrum into the infrared – a process called redshifting. Building on the legacy of the Teledyne Space Imaging technology in Hubble, MUSE can detect redshifted galaxies to a value of z > 6 – one to two orders of magnitude fainter than Hubble. As an Earth-based instrument, MUSE is not restricted by space payload parameters, so it benefits from a mirror over three times larger than Hubble, thus increasing sensitivity.

MUSE reexamined the groundbreaking Hubble Deep Field South and measured the distances to 189 galaxies. They ranged from some that were relatively close, right out to some that were seen when the Universe was less than one billion years old. This is more than ten times the number of measurements of distance than had existed before for this area of sky.

MUSE also took another look at the Hubble Ultra Deep Field image, measuring distances and properties of 1600 very faint galaxies, including the discovery of 72 Lyman-alpha galaxies. Since MUSE disperses the light into its component spectra, it can focus on the Lyman-alpha emission line. MUSE detected luminous hydrogen halos around galaxies in the early Universe, giving astronomers a new and promising way to study how material flows in and out of early galaxies.

Observing Planetary Nebula

A planetary nebula has nothing to do with planets. Rather, they are stellar remnants created after a star burns out. What’s left is an intricate structure of clouds of different temperature gases, lit up by a white dwarf in the center.

The Universal 'Cosmic Web'

After the Big Bang, much of the hydrogen gas that makes up most of the known matter of the cosmos collapsed forming colossal sheets. Past research supports the theory that those sheets broke apart creating thin filaments of a vast cosmic web which distributed the material needed to form galaxies.

MUSE focused on the SSA22 Protocluster, which lies about 12 billion light-years away from Earth in the constellation Aquarius. A protocluster is a group of hundreds to thousands of galaxies that are beginning to form a galaxy cluster, the largest structures held together by gravity in the universe. For the first time, MUSE captured the light emitted by hydrogen gas excited by ultraviolet rays from galaxies within the protocluster. The hydrogen gas around the young galaxies in the protocluster was arranged in long filaments extending over more than 3.25 million light-years.

The spectral data collected by MUSE, allows astronomers to map cosmic web filaments providing a new tool to understand the formation of galaxies and supermassive black holes.

Energy Source for Super Massive Black Holes

Image of the spiral galaxy NGC 1097. Located 45 million light-years away from Earth, this ring spans 5,000 light years across. The darker areas show dust, gas and debris, which are being funnelled into the supermassive black hole at its centre, forming an accretion disc around the black hole and radiating energy. Nearby dust is heated up and star formation accelerates in the area around the supermassive black hole, forming the star-bursting nuclear ring shown in pink and purple tones in the image. Credit: ESO/TIMER survey

Supermassive Black Holes (SMBHs) exist at the core of most galaxies, greatly influencing how they formed. The first stars are estimated to have formed 100,000 years after the Big Bang meaning that there needs to be sufficient material for stars to grow and combust into supernovas to form black holes. Until now, though, astronomers had not found dust and gas in high enough quantities during the early Universe to explain this rapid growth and the formation of so many SMBHs.

MUSE surveyed 31 quasars – highly active and luminescent SMBEs – at a distance of around 12.5 billion light-years; one of the largest surveys of its kind. This led to the discovery of large reservoirs of cool hydrogen gas that could have provided sufficient fuel to spur the formation of SMBHs. Several billion times the mass of the Sun, these clouds formed halos around the early galaxies that extended for 100,000 light-years from the central black holes. These results could explain how SMBHs grew so fast during the period known as the Cosmic Dawn.

Directly detecting these clouds was all but impossible with older technology due to the fact that the very bright quasars flood the surroundings with light. The high sensitivity iof spectral data collected by MUSE enabled this discovery.

What’s Next?

So far, MUSE data has been used in over 1,000 research papers, making it the most productive instrument on ESO’s VLT. This speaks well to its potential for fueling further discoveries.

Additionally, Teledyne Space Imaging sensors will also be employed in the forthcoming Echelle SPectrograph for Rocky Exoplanet and Stable Spectroscopic Observations (ESPRESSO) and Large Visible Sensor Modules on the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT).