In 1859, the Earth experienced the Carrington Event – the most disruptive solar storm ever recorded. It was so powerful that it fried telegraph systems throughout Europe and North America and cascaded auroras as far south as Colombia. When such an event occurs again, it could have disastrous results given our absolute dependence on electronics and satellite communications. The insurance firm Lloyd’s of London calculated that the fallout could cost up to $2.6 trillion in the United States alone.

More recently, a 1989 geomagnetic storm knocked out Canada’s Hydro-Quebec power grid, leaving millions of people without electricity for up to nine hours. Geomagnetic storms in 2003 caused airlines to reroute high-latitude routes to avoid high radiation levels and communication blackout areas; at an additional cost of $10,000 to $100,000 per flight. Additionally, these space storms endanger astronauts, and sensitive, high-cost scientific and communication satellites.

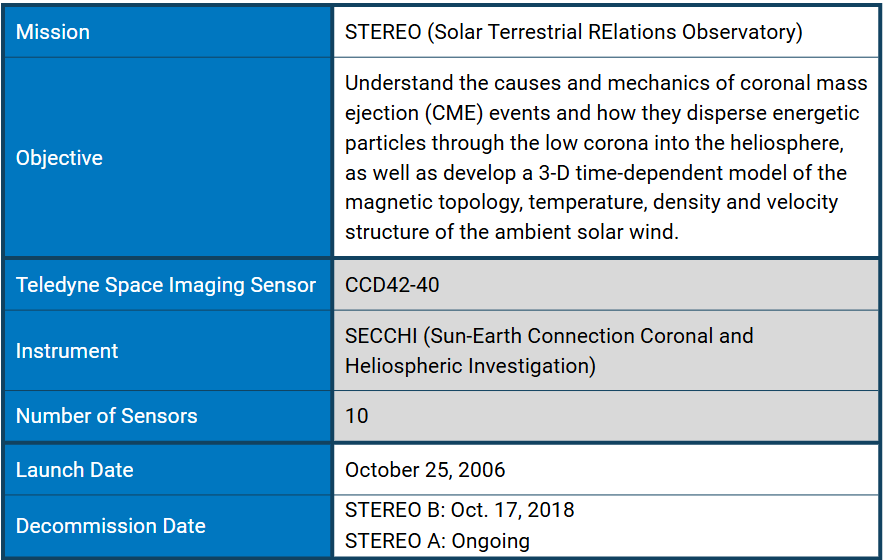

The source of these disruptive storms is explosions—called coronal mass ejections (CMEs)—generated by the magnetic forces churning inside the Sun. NASA dedicated its third mission in its Solar Terrestrial Probes program to studying these solar eruptions. The STEREO mission (Solar Terrestrial RElations Observatory) consisted of two nearly identical satellites that synchronized with the Earth’s orbit.

Credit: JHU/APL

Launched on the same rocket in 2006, it took six months to navigate the satellites into their challenging orbits with STEREO-A ahead of the Earth and STEREO-B behind the Earth. Configured as mirror images of each other, the twin satellites simultaneously collected slightly offset images which were combined together to create the first 3-D stereoscopic images of the Sun including the corona and 360-degree views of the Sun’s surface. These unique views–at image resolutions twice what could be achieved before–have allowed scientists to analyze CME activity and the structure of the corona with the goal of predicting space weather to better protect the Earth and our technology.

SECCHI

Each STEREO satellite is equipped with a suite of remote-sensing instruments called SECCHI (Sun-Earth Connection Coronal and Heliospheric Investigation). The system consists of an extreme ultraviolet imager EUVI, two white-light coronagraphs (COR1 and COR2), and two wide-field heliospheric imagers (HI1 and HI2). SECCHI collects images in four wavelengths of extreme ultraviolet light. Each wavelength captures plasma at different temperatures and distances starting at the solar surface and extending all the way to the interplanetary space between the Sun and Earth.

All five instruments on SECCHI use Teledyne Space Imaging CCD42-40, back-thinned, 2048 x 2048-pixel detectors to capture their respective images.

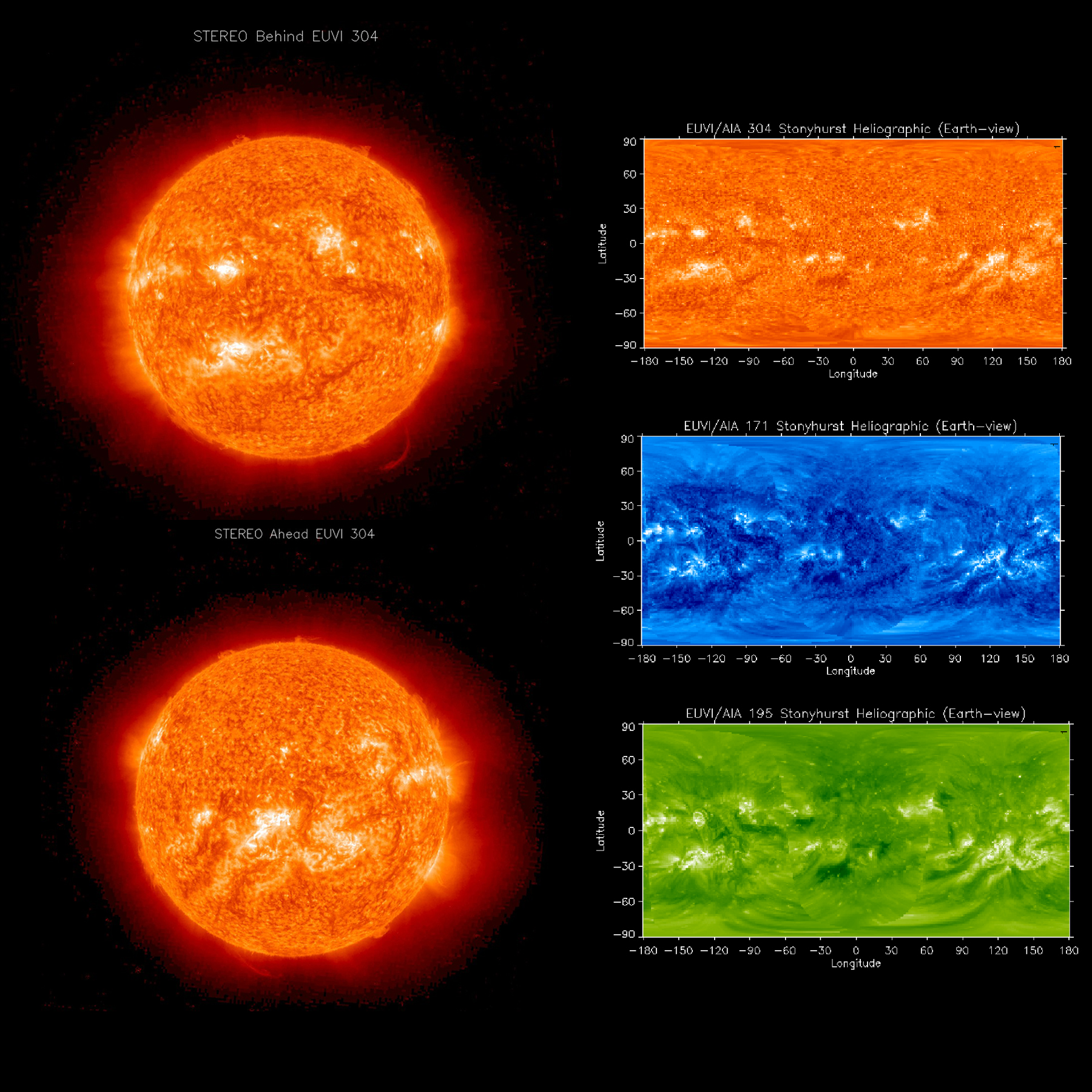

These images were all taken at just about the same time. The bright areas are active regions, often the sources of solar storms. Images from each wavelength are colourized so that they can be immediately identified. Credit: NASA

Viewing the Far Side of the Sun

The twin STEREO satellites slowly spread apart, with STEREO-A advancing ahead and STEREO-B falling behind. This separation allowed scientists to examine the far side of the sun facing away from the Earth rather than waiting for it to rotate into view. As it takes the Sun 27 days to rotate, this could create a problem for predicting CMEs.

A 360-degree view of the sun allows for a complete view of solar activity. Left: views of the sun from STEREO. Right: 360-degree maps are generated with combined views from the the Solar Dynamics Observatory. The wavelengths on the right are from top down: 304 Angstroms, 171 Angstroms, and 195 Angstroms. Credit: NASA

A 360-degree view of the sun allows for a complete view of solar activity. Left: views of the sun from STEREO. Right: 360-degree maps are generated with combined views from the the Solar Dynamics Observatory. The wavelengths on the right are from top down: 304 Angstroms, 171 Angstroms, and 195 Angstroms. Credit: NASA

Discovered the Helical Structure of Coronal Jets

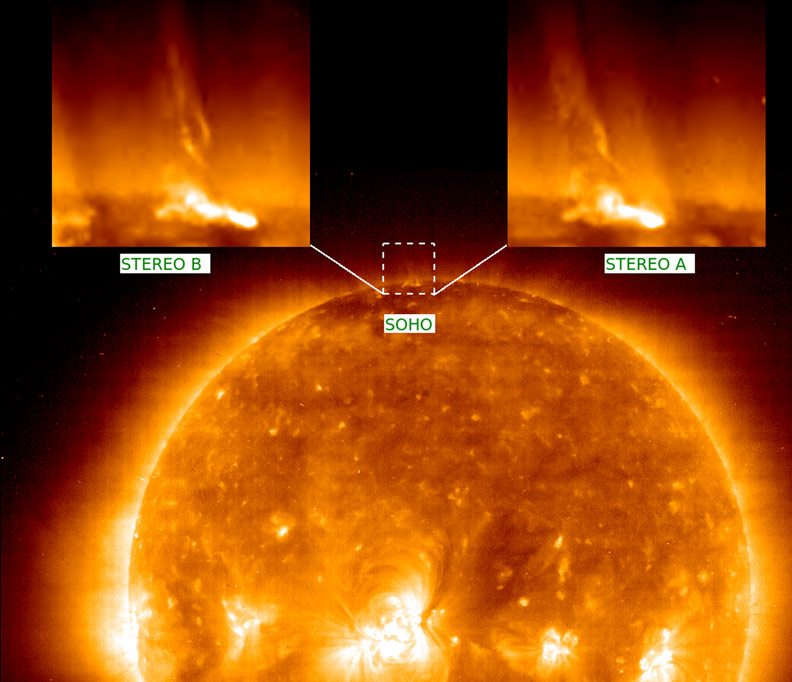

Credit: NASA

Coronal jets are small, short-lived ejections of plasma that shoot about a million tons of matter through the atmosphere at about a million miles per hour. The jets are believed to contribute significantly to the mass flow constantly ejected by the Sun, known as the solar wind.

In 2007, a unique polar coronal jet observation was made by STEREO. Analysis of the stereoscopic images revealed conclusive evidence of the helical structure in the jet. Further numerical modeling determined that the jets are formed by magnetic fields that twist tighter and tighter until they become unstable – similar to an overwound spring. When the writhing fields come into contact with nearby untwisted fields that extend into the solar wind, the twist is transferred to those very long field lines. The twist then rapidly leaves the Sun, pushing the plasma outward at high speed.

Predicting Stealth CMEs

CMEs usually take one to three days to travel the 93 million miles to Earth, giving us enough time to redirect satellites and route power grids to limit the potential damage. But many CMEs occur higher in the corona and do not produce obvious signs close to the photosphere. These 'stealth CMEs' were only detected when they reach Earth.

Scientists at the International Space Science Institute (ISSI) looked at four stealth CMEs that were luckily captured by STEREO between 2008 and 2016. Their point of origin was successfully traced because of the unique imaging angle of the STEREO spacecraft. Comparing images taken 8 to 12 hours apart–images not necessarily taken by STEREO–revealed very slow, and subtle changes in the lower corona. This new imaging technique revealed previously undetected tiny dimmings and brightenings on the Sun where the stealth CMEs started. It was concluded that the technique can be used for the early detection of risky stealth CMEs headed for the Earth.

Understanding Comets

Like asteroids, comets are made of elements leftover from the formation of our solar system 4.6 billion years ago. Accordingly, these frozen balls of gas, rock and dust may contain important clues about our solar system’s early history. When a comet’s elliptical orbit brings it close to the Sun, the heat partially melts it, releasing dust which streams behind the comet, forming two distinct tails: an ion tail carried by the solar wind and a dust tail. Understanding how dust behaves in the tail can teach scientists about similar processes that formed asteroids, moons, and planets.

Oliver Price, a planetary science PhD student at University College London’s Mullard Space Science Laboratory in the United Kingdom, developed a new image-processing technique to mine through the wealth of data about comet tails. Note that the black and white STEREO images feature sharp contrast as compared to the SOHO images. Credit: NASA Goddard

Unfortunately, communication with STEREO B was lost on Oct. 1, 2014, due to multiple hardware anomalies affecting control of the spacecraft's orientation. Despite re-establishing contact on Aug. 21, 2016, it was found that the solar panels were not pointed directly at the Sun greatly reducing operational battery power. It was determined that periodic recovery operations would cease with the last support on October 17, 2018.

STEREO-A continues to operate normally, and its current mission extension was based on using just one spacecraft. The planned research is to characterize space weather throughout the inner heliosphere, support 360-degree coverage of the sun (along with SDO and SOHO), and improve the understanding of phenomena from the sun's atmosphere all the way to the edges of the Solar System, information crucial to future interplanetary space travel.